Noisy jackdaws known for suddenly taking flight in their thousands only do so after calling out to each other louder and louder in a type of bird democracy, according to a study.

The racket made by the blackbirds is believed to be a form of “consensus decision-making” – something that may draw comparisons with the uproarious House of Commons.

While the huge noise may sound chaotic, experts believe the cacophony is actually the creatures each casting a ‘vote’.

Researchers from the University of Exeter recorded the rising noise of jackdaw calls that happens before mass departures at various roosts in Cornwall.

By combining this with tests in which pre-recorded jackdaw calls were played at a colony, the team found evidence that the birds’ calls are used to form a group decision.

“After roosting in a large group at night, each jackdaw will have a slightly different preference about when they want to leave, based on factors like their size and hunger,” said Alex Dibnah, who led the study as part of a Masters by Research at Exeter’s Penryn Campus in Cornwall.

“However, it’s useful to reach a consensus. Leaving the roost together has various benefits, including safety from predators and access to information such as where to find food.

Sadiq Khan demands explanation from police after ‘smoking gun’ pictures – as Shapps denies PM was partying

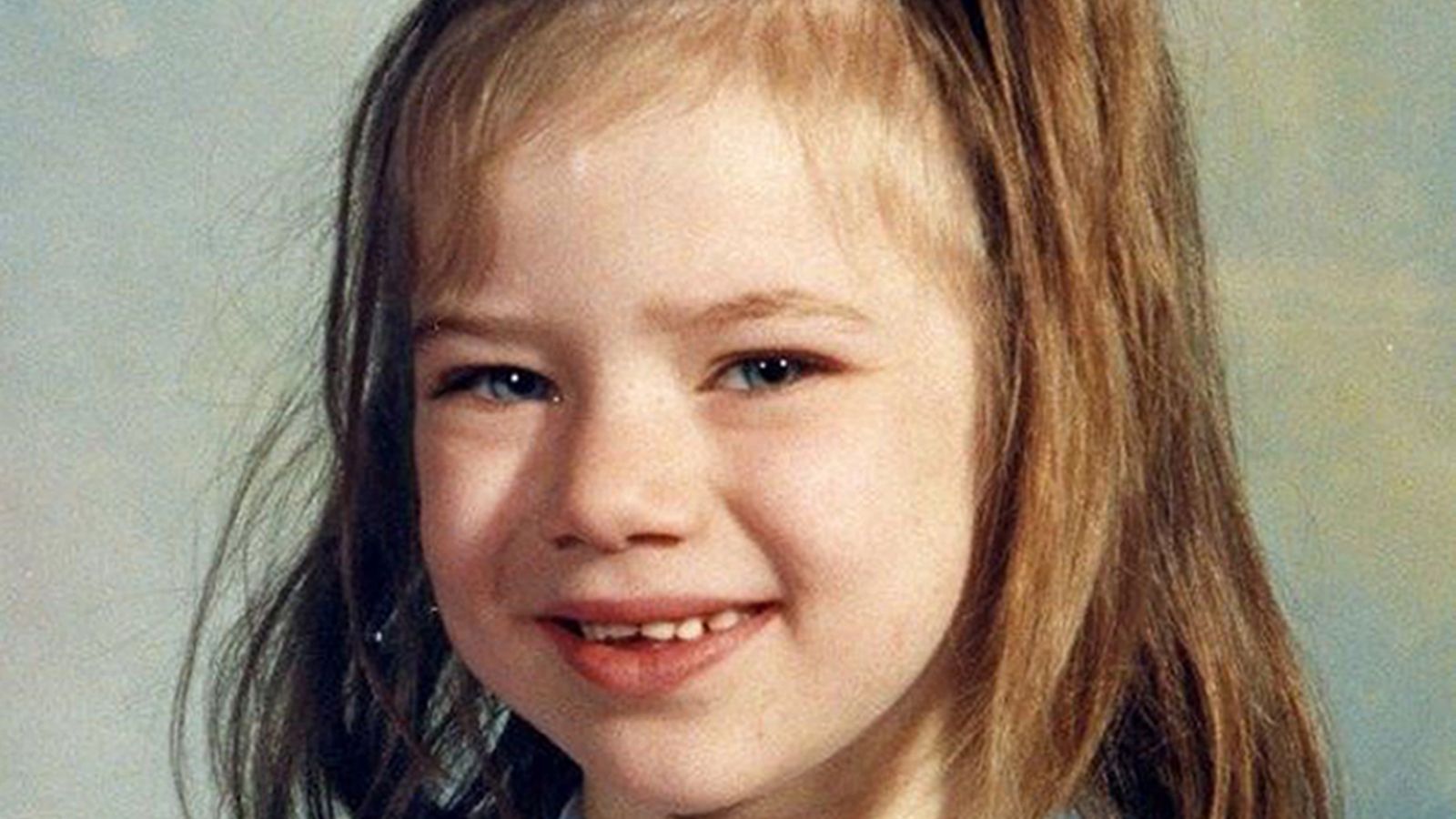

Kemarni Watson Darby: Man who murdered partner’s three-year-old son jailed for at least 24 years – as boy’s mother gets 11 years

Politics live: Boris Johnson suggested Sue Gray drop her partygate report during private meeting, according to sources

“Our study shows that by calling out jackdaws effectively ‘cast a vote’ and, when calling reaches a sufficient level, a mass departure takes place.”

Jackdaws roost in groups of hundreds or even thousands and it is common for most or all of the birds to take flight suddenly around sunrise.

The research team found that such departures happened almost instantly, with all departing birds in the air within less than five seconds on average.

Commenting on the wider significance of the research, Professor Alex Thornton said: “It helps us to understand how really large groups of animals can coordinate their actions – something that has rarely been tested in detail before.”